Kazuo Ishiguro Sees What the Future Is Doing to Us

With his new novel, the Nobel Prize-winner reaffirms himself as our most profound observer of human fragility in the technological era

To hear more audio stories from publishers like The New York Times, download Audm for iPhone or Android.

On a bright, cool Saturday in late October 1983, the growing prospect of thermonuclear war between the world’s two superpowers drew a quarter million people out into the streets of central London. Among them was a young writer named Kazuo Ishiguro, who’d recently published his first novel. Ishiguro’s mother had narrowly survived the atomic bombing of Nagasaki in 1945, so his presence at the march that day felt like a matter of personal duty. Along with a group of like-minded friends, he chanted slogans demanding that the West renounce its nuclear arsenal — the hope being that the East would quickly follow suit. As they made their way past Big Ben to Hyde Park, holding signs and waving banners, a current of euphoria spread among the crowd. Synchronized protests were taking place all across Europe, and for a brief moment it seemed possible to believe that they would actually make a difference. There was just one problem, as Ishiguro saw it: He worried that the whole thing might be a terrible mistake.

In theory, unilateral disarmament was a nice idea; in practice, it could backfire catastrophically. Perhaps the Kremlin would respond to a nuclear-free Europe in the way the demonstrators foresaw, but it wasn’t hard for Ishiguro to imagine a less harmonious outcome. Even as he recognized their good intentions, he feared the marchers were succumbing to the disorienting lure of mass emotion. His parents and grandparents had lived through the rise and fall of fascism, and he grew up listening to stories about the dangerous power of crowds. Britain in the 1980s was a far cry from Japan in the 1930s, and yet he recognized common denominators: tribalism, an impatience with nuance, the pressure placed on ordinary people to take political sides. Ishiguro, a mild, deliberative person, felt this pressure intensely. He didn’t want to wake up at the end of his life only to realize that he’d given himself to a misguided cause.

These anxieties found an outlet in the novel he was writing at the time, “An Artist of the Floating World.” Masuji Ono, the book’s narrator, is a man who waits too long to ask himself whether he might be backing a misguided cause. An aging painter in late-1940s Japan, Ono has been suffering from moral whiplash: His monumental artworks celebrating Japanese imperialism, at one time the source of honor and renown, have taken on a shameful meaning in the democratizing postwar era. Looking back over his life, he tries to come to terms with his decisions. Nietzsche once distilled the workings of psychological repression thus: “Memory says, ‘I did that.’ Pride replies, ‘I could not have done that.’ Eventually, memory yields.” In Ishiguro’s novel, the tug of war between pride and memory plays out behind a screen of glazed eloquence as Ono uncovers the things he has carefully hidden from himself.

At 66, Ishiguro is now approaching the age of the disgraced propagandist he imagined in his youth. To say that the life lived in error he once feared has not come to pass would be understating the matter — something Ishiguro, a virtuoso of restraint, has been doing for almost 40 years. In 2017, he won the Nobel Prize in Literature, the closest thing an author can get to outright existential validation. Announcing the award, the Swedish Academy described him as someone “who, in novels of great emotional force, has uncovered the abyss beneath our illusory sense of connection with the world.” Ono, in “An Artist,” or Stevens, the English butler who narrates “The Remains of the Day,” which was awarded the 1989 Booker Prize, are men who have ever but slenderly known themselves. Only late in life does Stevens recognize the mess he has made of things, freezing out the woman he loves and throwing away his best years — the period between the two world wars — in service to a Nazi-sympathizing master.

Ishiguro was laden with prizes long before the call from Stockholm came through, but acclaim has never stopped him from asking the questions that troubled him on the march in 1983: What if I’m wrong? What if I’m making a terrible mistake? On the evening of Dec. 7, 2017, he confessed to the audience who gathered to hear his Nobel lecture that he’d begun to wonder whether he’d built his house of fiction on sand. “I woke up recently to the realization I’d been living for some years in a bubble,” he said from behind the gilt-inlaid lectern. “I realized that my world — a civilized, stimulating place filled with ironic, liberal-minded people — was in fact much smaller than I’d ever imagined.” The raucous discontent that Brexit and the rise of Donald Trump were laying bare had forced him to acknowledge a disturbing reality. “The unstoppable advance of liberal-humanist values I’d taken for granted since childhood,” he said, “may have been an illusion.”

Ishiguro’s new book, “Klara and the Sun,” his first since the Nobel, picks up more or less where his acceptance speech left off. The novel is set in a near-future America, where the social divisions of the present have only widened and liberal-humanist values appear to be in terminal retreat. Appropriately enough, our window onto this world is not a human being but an animatronic robot powered by artificial intelligence. Its name is Klara — or should that be “her” name? On this choice of pronoun hinges the moral burden of Ishiguro’s tale. The book addresses itself to an urgent but neglected set of questions arising from a paradigm shift in human self-conception. If it one day becomes possible to replicate consciousness in a machine, will it still make sense to speak of an irreducible self, or will our ideas about our own exceptionalism go the way of the transistor radio?

Unlike his ill-at-ease narrators, Ishiguro is a droll, self-deprecating presence, secure in his gift and the uses he has put it to. “If it wasn’t for my screenplay, I think it would have been a pretty good film,” he told me recently. He was speaking of “The White Countess” (2005), an all-around flop on which he joined forces with James Ivory and Ismail Merchant. (The duo had better luck with “The Remains of the Day,” a nominee for Best Picture at the 1994 Academy Awards.) Perhaps modesty comes easier when everyone is telling you how remarkable you are — he seems to average around a prize a year — but there is something about Ishiguro, a sort of twinkling poise, that makes you feel that he would be the way he is in any simulation of his life. “He’s very at peace with himself,” Robert McCrum, a longtime friend and former editor, said. “There’s no darkness in him. Or if there is, I haven’t seen it.”

As a man is, so he writes, and Ishiguro’s sentences have nothing to prove. In the hands of some of his contemporaries — Martin Amis, say, or Salman Rushdie — the novel can sometimes feel like a vehicle for talent; high-burnish prose comes at the reader in a blaze of virtuosity, but the aesthetic whole isn’t always equal to the sum of its parts. Ishiguro, a practitioner of self-effacing craft, takes a contrary approach. At first glance, his books can appear ordinary. “It seems increasingly likely that I really will undertake the expedition that has been preoccupying my imagination now for some days” is the far from dazzling first sentence of “The Remains of the Day.” The real action happens between the lines, or behind them, as when Stevens justifies his taste for sentimental romance novels on the grounds that they provide “an extremely efficient way to maintain and develop one’s command of the English language.” That they might also provide a dose of wish-fulfillment to a disconsolate, middle-aged bachelor is something we are left to infer for ourselves. It is not for nothing that Ishiguro has named Charlotte Brontë as the novelist who has influenced him most. From “Jane Eyre,” he learned how to write first-person narrators who hide their feelings from themselves but are transparent to other people. Rereading the book a few years ago, he kept coming across episodes and thinking, Oh, my goodness, I just ripped that off!

Ishiguro’s latest novel continues this tradition of beneficent theft. Klara, an A.F., or Artificial Friend, is a sort of mechanical governess in search of a post. We first meet her (we’ll go with “her” for now) in a storefront window, where she is desperately hoping to catch the eye of a would-be owner. Meanwhile she has to content herself with the spectacle of street life, and one pleasure of the book’s opening section comes from watching Klara’s newly awakened synthetic consciousness expand in real time. First she gets to grips with things like physical space, color and light (A.F.’s run on solar power), but before long she is wrapping her head around more abstruse realities, like the rigid caste system that defines the society of which she is at once a product and a witness.

“It feels more fragile today than it ever has done in the time since I’ve been conscious,” Ishiguro said of liberal democracy. He was speaking to me over Zoom from his home in Golders Green in North London. From where I sat, in Los Angeles, liberal democracy didn’t look too sturdy either. It was mid-November, two weeks after the presidential election had finally been called for Joe Biden, but Donald Trump and his supporters continued to resist this reality.

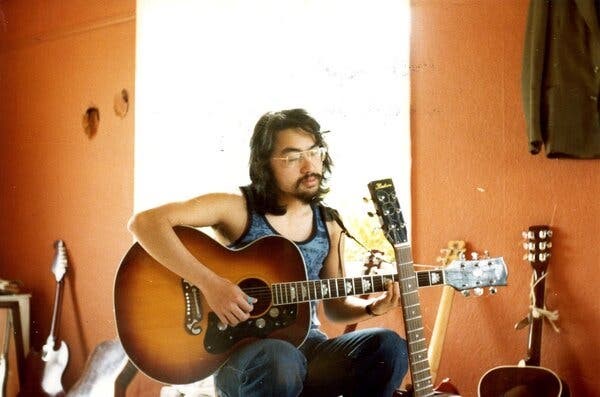

In his late teens and early 20s, when he was trying to make it as a singer-songwriter, Ishiguro had shoulder-length hair and a bandit-style mustache and went around in torn jeans and colorful shirts. These days the facial hair and flowing locks are gone, and he dresses exclusively in black. (“He hates shopping, but he wants to look cool, so at one point he just bought a thousand black T-shirts,” his daughter, Naomi, told me.) He didn’t look uncool this evening, hunched in front of the monitor in his sable shirt and rimless glasses. To his right was a bookshelf lined with Penguin Classics, to his left (as he obligingly revealed when I asked him for a brief tour), a spare bed crowded with stuffed animals.

Ishiguro in Kent, England, in the summer of 1977. Before turning to writing, he hoped to become a singer-songwriter.Credit…From Kazuo Ishiguro

Ishiguro likes to compare his generation, born at the start of the postwar era, to Buster Keaton’s character in “Steamboat Bill Jr.,” who, in the famous scene, is standing in front of a house when its facade collapses on top of him. He’s saved by an open upstairs window, which falls clean over his oblivious figure. “We don’t realize what a narrow miss we had,” Ishiguro said in his measured, unemphatic voice. “If we’d been born just a little bit earlier we would have gone through the war, the Holocaust — all that savagery.” Instead they inherited a world of unparalleled material comfort and reached maturity at the zenith of the sexual revolution. “For my daughter’s generation, I don’t feel things are so secure,” he said. “In the West, since the end of the Cold War, we’ve allowed massive inequalities to develop, which are leading substantial numbers of people to think, Well, maybe this isn’t for us.”

Kazuo Ishiguro Sees What the Future Is Doing to Us – The New York Times (nytimes.com)